Contents:

Phylum Cnidaria (Coclenterata)

Features

Type of organism

- Cnidarians, formerly known, together with the Ctenophora (sea-combs), as the Coelenterata, include sea-anemones, corals and jellyfishes.

- They are usually marine although there are a few freshwater species (e.g. Hydra sp.). There are two basic forms of cnidarian.

- The columnar, sac-like polyps have an upward-facing mouth around the end of the radial axis, surrounded by tentacles.

- Most polyps are sessile but some move by gliding (pedal creeping), somersaulting or burrowing into the substratum.

- Medusae resemble umbrellas and are usually pelagic (free-swimming), swimming mouth-down with the tentacles floating outwards.

- Sizes of cnidarians range from the microscopic to 2 m for polyps; the medusae of the sea blubber Cyanea sp. can attain 3.5 m diameter with 30 m tentacles.

- Coral reefs, below the surface of shallow seas, are largely made up of the CaCO3 exoskeletons of several species of cnidarians and of other calcium precipitating organisms such as certain algal species.

- The earliest cnidarians recorded are hydrozoans such as Ediacara sp., from 700 million years B.P. By the Cambrian period, all modern cnidarian groups were extant, although the phylum is arguably on an evolutionary cul de sac.

Body plan

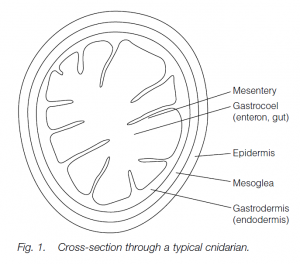

Cnidaria are radially symmetrical animals with two body layers, an outer epidermis (ectoderm) and an inner gastrodermis (endoderm) which lines the gut, a condition known as diploblastic. Between the gastrodermis and the outer epidermis lies a gelatinous mesoglea containing some loose cells. Support is effected by the hydrostatic pressure in the gastrocoel (which acts as a hydrostatic skeleton when the mouth is closed), by the mesoglea and, in some polypoid cnidarians, by a calcareous exoskeleton.

Locomotion

Muscle cells lie in the mesoglea. Sheets of radial and circular muscle fibers effect medusal swimming. Polyps are sessile but can move by burrowing, somersaulting or pedal creeping.

Feeding

The gastrocoel, lined with endodermal cells, is the sole body cavity: it serves as the gut. Cnidarians are carnivores: they possess stinging cells, nematocysts, on their tentacles. The nematocysts discharge when undulipodia on the surfaces of the tentacles are stimulated. Food enters the gut via the mouth. The absorptive surface of the gut is increased by mesenteric folds. There is no anus, so waste is discharged through the mouth. This condition is known as an ‘incomplete’ gut. Many cnidarians possess intracellular, photosynthesizing dinoflagellates as symbionts; some freshwater hydras have similar symbiotic relationships with chlorophyte algae. The presence of such symbiotic organisms has been shown to enhance the growth of the cnidarians.

Co-ordination

Control and integration is facilitated by a nerve net with nerve cells possessing unmyelinated, naked cells with highly branched fibers.

Reproduction

Gonads are aggregations of gametes; fertilization is external. Development is usually via a planula larva. Asexual reproduction by budding is common, particularly in colonial forms.

Classes

Three classes of cnidarian are recognized: the Hydrozoa, the Scyphozoa and the Anthozoa.

Class Hydrozoa

- The 3100 species of Hydrozoa are mainly marine and include colonial forms and the fire corals; there are also a number of freshwater hydras.

- Colonial forms (e.g. Obelia sp.) may exhibit considerable polymorphism among the polyps, with polyps being specialized for functions such as feeding, reproduction and defense.

- This trend is seen most developed in siphonophorans such as Physalia sp., the Portuguese man-o’-war, where a float (filled with 90% carbon monoxide) aids buoyancy.

- Reproduction may be by asexual budding of polyps off parent polyps, but sexual reproduction is observed too.

- A medusa forms from a bud on the polyp colony; the medusa floats away and produces free-swimming eggs and sperm.

- Following fertilization and cell division, a free-swimming, mouthless, ciliated planula larva develops which later metamorphoses into a polyp.

Class Scyphozoa

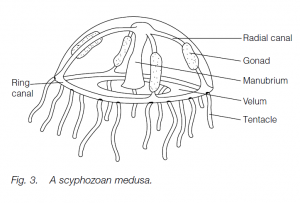

The class Scyphozoa (about 200 spp.) comprises the jellyfishes whose dominant life-form is a free-living medusa (Fig. 3). The fertilized egg develops into a planula larva which metamorphoses into a polyp: this continually buds over several years to form free-swimming male or female medusae. (Some oceanic scyphozoan planulae metamorphose directly into medusae, thus bypassing the polyp stage.)

Class Anthozoa

The Anthozoa (about 6200 species) are the sea-anemones, sea-pens, sea-pansies and the soft and stony corals. They are marine animals, solitary or colonial, existing as hermaphrodites or as separate sexes. Stony corals are important constituents of coral reefs. Anthozoan eggs usually develop into planulae which settle and metamorphose into polyps. No medusae form. Viviparity is observed in some species in which the planula is retained in the body, a mature polyp being released.

Related phylum

Phylum Ctenophora (sea-combs or comb-jellies)

There are about 90 species of ctenophores; these marine, diploblastic animals possess a mesoglea and a branching gastrocoel. Eight paddle-like comb plates (ctenes) with aggregates of external cilia give a radial symmetry on which two tentacles superimpose a bilateral symmetry. Stinging colloblasts are the equivalent of the cnidarian nematocysts. They possess true muscles but have only a nerve net. Many are phosphorescent, and symbiotic algae within the combjellies can give the latter vivid colors. An example of a ctenophore is Cestum veneris, Venus’ girdle.